|

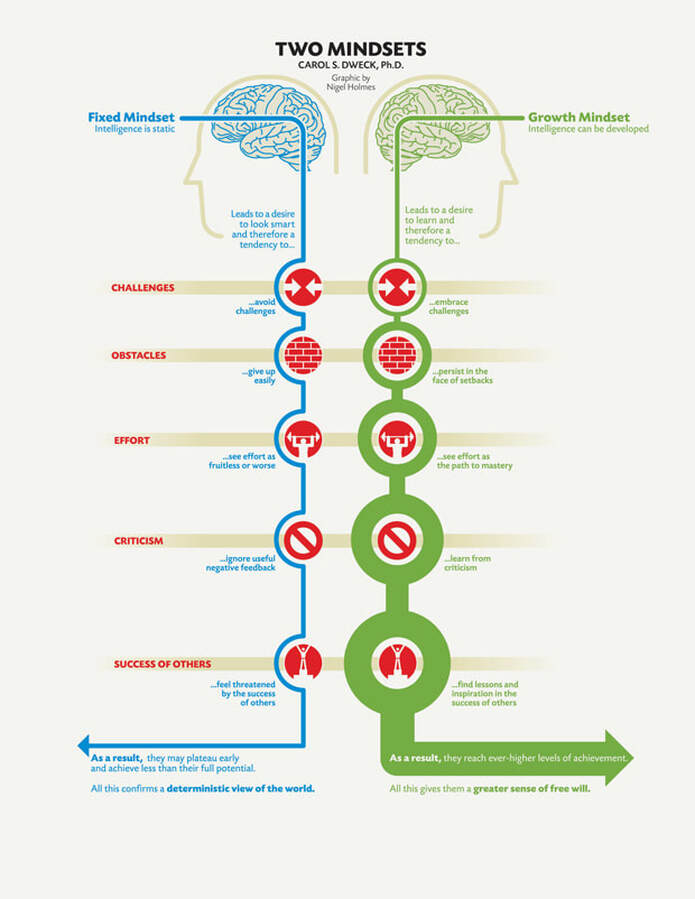

JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE:

Imagine the student whose teacher suggests she move to the honors class, the tennis player who is asked to play on the more competitive team or the musical talent who is invited to play on a big stage. Often we think, what an amazing learning opportunity this will be for the child or teen to be challenged and develop their abilities. While some kids may agree and rise to meet the challenges (albeit with an appropriate level of nerves) and meet the task head on, others may be scared, shrink or not even try. It can be too scary to try, perhaps fail, and have it be found out that they actually aren’t as good as everyone says they are, as good as they thought they were. These kids believe that their ability is who they are. I am either good at this or I’m not. I’m a winner or a failure. It’s not, “Wow, that was hard. It may have been a setback (or an exciting challenge). Let’s go back and try again.” Some respond to failure, difficulty or challenge as an affront to themselves. I’m not good. I can’t do it. I give up. I don’t want to try. Others respond with curiosity, perseverance and tenacity. I love a challenge. What can I learn from this? What can I do differently next time? And of course there are some gray areas in between. Parents have come to me saddened by their child’s quickness to quit, their lack of desire to try something new, challenging or slightly out of their comfort zone, or even giving up on something they used to love. Where does this apparent lack of confidence come from? Psychologist and professor Carol Dweck in her seminal work on fixed and growth mindsets might lead us to some answers. Those with a fixed mindset tend to believe that one’s abilities are innate character traits that people are born with, and no amount of effort will change this. The thought is that if I only have a fixed amount of intelligence, talent or ability then I better prove that those abilities are high because there is nothing I can do to make them better. Further, there is a desire to avoid failure at all costs, lest it be found out that I am not smart, talented, athletic or good. Where does a fixed mindset come from? Often from too much generalized praise: “Good job!” “You’re so smart.” “You’re an amazing athlete.” Kids who are told this over and over again can come to believe that this is who they are. The child or teen can feel so much pressure to live up to this idea of “who” they are that they are afraid to try more challenging activities. What if they fail or it’s found out they actually don’t have those abilities? Sometimes being born with these natural abilities, such as a propensity toward academics, an ease with music or a naturally athletic body, can be more of a curse than an advantage. If I am born this way, I will always be this way. My ability is fixed. And if it is fixed, or “carved in stone” as Dweck says in her book “Mindset,” challenges can become scary: “You are either smart or you aren’t and failure means you aren’t.” Those with a growth mindset have a more open mind about their abilities. They believe talent can be cultivated by effort, hard work and practice. They see failure as a learning opportunity, which gives them room to grow. Where does a growth mindset come from? It comes from specific praise, and kids being praised for their effort: “You worked really hard at that.” “You really worked at your passing today.” “I noticed how you stuck with that hard math problem until you figured it out.” Dweck’s studies show that children who are praised for their effort choose more challenging tests and do better on subsequent tests. Those who are told they are smart choose tests that are easier in order to confirm their intellect, and their performance does not improve. When kids are told they are smart or talented or athletic they get the message “look good, don’t make mistakes,” and so they shy away from challenges or anything that might make them look bad. As Dweck says, the name of the game becomes “arrange successes and avoid failure at all costs.” What is important as parents is that we don’t brush over or try to quickly ameliorate failure. Often we are afraid to talk about failure for fear that our kids will feel bad. Yet if we don’t talk about what went wrong, how can we learn from it? Dweck believes that rather than giving up, the way to bounce back from failure is to work hard and try again. It’s the idea of persistence, a trait, as authors Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman write in their book “Nurture Shock,” that allows people to rebound and sustain motivation even if the gratification, or reward, is delayed. Bronson and Merryman go on to explain that there is an actual message in the brain that is sent when there is a lack of immediate reward. It says, “Don’t stop trying, there is dopamine on the horizon.” But the release of too much dopamine, the feel-good chemical our brain emits when we get a reward, can backfire: “[A] person who grows up getting too frequent rewards [or blanket praise] will not have persistence, because they’ll quit when the rewards disappear.” You can see why too much praise can lead to a lack of motivation. And, as Dweck notes, when we praise ability we take the outcome out of children and teens’ control. When we emphasize effort, kids can see they can actually play a role. It gives them a sense of mastery and agency. It’s hard to enjoy an activity when your entire focus is on looking smart, athletic or talented. And it’s certainly hard to put yourself out there in public and even try. If our kids have interest or passion in something — a love of learning, sport or the arts — we hope to see them follow their passions. Not because we want to see the outcomes, but because it brings them a sense of joy, accomplishment or pride. What kids need is a strategy for handling failure and a belief that they can control their outcomes. As Dweck says, “the view that you adapt for yourself profoundly affects the way you lead your life.” Stay tuned this school year as I apply these ideas more specifically to homework, motivation, sports and more. Want to learn more on mindsets and the inverse power of praise? Go to my resource page at GGFWyo.com and scroll down to the section on mindsets. JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE:

Breaking curfew. Telling you they are spending the night at a friend’s house whose parents are home and you later find out they were at a party where alcohol was flowing freely. Not doing their assigned chores. Going out and binge drinking until blacking out. Sneaking out of the house in the middle of the night. Vaping, smoking pot or doing other drugs. Staying up until 3AM in their rooms playing video games. Talking back. Being mean, rude or disrespectful. Disobeying family rules or agreements. Pure defiance. Teen rebellion can run from the relatively innocuous to the extreme. Like it or not, it is a normal part of teen development, and, like it or not, some level of teen rebellion is actually healthy and serves a positive purpose. As I wrote in my June 1 column titled “The gentle push and pull of raising teens”, teens are doing the important work of individuating from their parents and developing a sense of autonomy. As Christine Carter, author of “The New Adolescence ” writes, teens no longer need their parents to manage their lives. “Parents who are too controlling – those who don’t step down from their manager roles – breed rebellion.” One of the main reasons kids break rules is not because they are bad kids but because they want a sense of control over their own lives. Rebellious behavior can also stem from other things including adolescents’ propensity toward risk taking – something I will discuss in a future column. Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman report in their book “Nurture Shock”, that “it’s essential for some things to be ‘none of your business’”. Lying or withholding information helps adolescents carve out an identity separate from their parents. Think about it – how much did your parents know about your whereabouts and activities when you were a teen? What’s important is that this need for autonomy doesn't start at age 15. It starts at age 11 and even younger. We need to be able to give our kids the reins of their own lives as early as possible in an age appropriate way. Despite the inevitable challenges, we as parents can help guide our teens through this stage using a few basic principles. It is important to note that some situations need intervention immediately, including threat to self, threat to others and declining mental health. It is important to seek professional help in these situations. Setting rules. As Bronson and Merryman write, parents who are warm and have open conversations with their kids are those who are the most effective in setting rules that kids will follow. It’s not that these parents set an abundance of rules, but more that they’ve come up with agreements with their kids about certain key activities, talked about why the rules are in place, and allowed their teens autonomy and decision making over other aspects of their lives. Balance between strict and permissive. While consistent rules are important, listening to your teen’s arguments and adjusting when it seems reasonable is equally as important. When kids feel heard, and when they are given concessions or amendments to rules when reasonable, they are more likely to adhere to their parents’ expectations. This is not being a pushover parent who concedes in order to avoid conflict, wants to save their child from disappointment or is afraid their child won’t like them. It is being a parent who listens, takes the time to make a thoughtful and reasonable judgment, and trusts that their child, who has shown they are ready, is able to handle the next stretch of the rubber band. As Bronson and Merryman say, this approach allows the “rule-setting process to be respected” and teens will actually divulge more and lie less. Be OK with some arguing. While we parents may describe the arguing about limits and boundaries harmful to the relationship, teens actually find it to be productive. This is where they can voice their opinion, learn conflict resolution, hear their parent’s reasonable point of view, and even ease their parent’s fears by showing their parents how capable they really are. When concessions are made, teens can then feel empowered, respected and significant. The message they get is that their parents believe in them. Allow natural consequences to play out. Unless morally or physically dangerous, allow the natural consequences of their actions to teach them what they don’t want to be taught from you. Allow your teens appropriate levels of independence once they’ve shown they are able to take responsibility for themselves and their actions. What might this look like in practice? There may be a special circumstance where you bend their 11 PM curfew until midnight this one time. Or your teen has shown responsibility and you change it altogether. Or approach them first: “You’ve been consistently coming home on time and have shown accountability for your actions. It seems like you might be ready for a later curfew.” Similarly, if you find your teen is unable to handle the new latitudes they have been given, you can rein it back in: “It seems like you are having a hard time with the later curfew you’ve been given. We’re going to have to make it earlier until you can show us you can take the responsibility to come home on time.” Understanding and Empathy. As psychologist Leon Seltzer points out, understanding teen development and the rebellious stage most go through can help you meet their needs with calm, care and empathy. Blowing your top will only exacerbate the situation. Hard as it may be, try not to take their words and behavior personally. Take a look inside. Consider what is making you feel the need for such control. Ask where can you trust? Where can you let go? Have you taught your teen the skills she needs to meet the reasonable expectations you have? Is the relationship built upon mutual respect? Can you loosen the reins to allow your teen to grow into the independent capable being that he is? Take a leap of faith. Hold limits where essential. Loosen them where you can. You’ll soon find that your teen will emerge from this stage with a sense of confidence in who they are and respect and appreciation for you. JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE:

Imagine the relationship you have with your child or teen as if the two of you are attached together by a rubber band. Using Vicki Hoefle’s rubber band analogy, you can see that there is no stretch in that rubber band when you are raising an infant. You keep your baby close and make all the decisions for them. Then, as your baby grows into a toddler, you allow that rubber band to stretch just a bit so your child can go out and explore, but you have your hand held tightly around that band so you can yank it in at a moment’s notice if needed to keep your child safe. In the middle years you allow an ebb and flow in the rubber band as your child gains more skills and you gain more confidence. There is a bit more ease in the relationship and for the most part you trust your child to listen to your guidance and make good decisions, so you allow the rubber band to stretch. And then puberty hits and children change. Their brains, hormones, bodies and attitude change, and they begin to individuate from us in a way that we are not prepared for. They want more freedom, are wired to take more risks, want to make their own decisions, often prefer their friends over us, are exposed to more in the adult world and may react to us in less than desirable ways. And because we are not prepared and the risks seem so high, we get scared. So what do we do? We yank on that rubber band hard, pull it in tight and treat our kids as if they are toddlers again watching over their every move. And here is where there is choice. We can communicate openly with our tweens and teens, co-create reasonable boundaries and hold them accountable, tame some of our fears, and begin to trust: we allow the rubber band to stretch. We can learn to stand in this ebb and flow with our teens and get comfortable. If we allow our teens the space, they will return on their own. We stand steady and they will return because we are not grabbing hold. Or, fueled by our fear, we can yank and yank and yank on the rubber band, and try to keep them close. Our relationship will then become a tug of war with our teens who want to move toward the adult world and discover their own path. And as much as this is hard for us, they want to do it without our constant presence. Here’s the thing: if we hold that rubber band too tight, they may pull so hard in the other direction until the rubber band snaps completely. Children are born with an innate desire to individuate from us – to become their own people – from the moment they first roll over in the crib. When they learn to walk, we let them fall down and delight in their new found abilities and determination. When they learn to drive or start going to parties we get nervous. I can hear you say, “the dangers of teenage risky behavior have much higher consequences than a toddler falling two feet to the ground”, and I completely understand the truth to this. The consequences of crashing a two ton vehicle can be massive so of course we need to teach them well, while giving freedom within reasonable limits. If we don’t hold on to the rubber band at all, we lose valuable opportunities for our kids to learn how to self-manage, take responsibility and live a healthy balanced life. What if we allow the rubber band to stretch within limits and in an age appropriate way; give our kids sufficient responsibilities; trust them to do things on their own; teach them the skills they need and allow them to pick themselves up after they’ve made mistakes; have open conversations with them about all that life can throw their way and listen to their opinions and allow them a say? Then it is highly likely that we have prepared them to handle a fair amount of slack in the rubber band. I am not saying that you don’t have limits. And I understand that a teen’s brain is not fully developed until their mid 20’s. But as they mature and show they can make good decisions, these limits change. It is freedom with responsibility. And because you have given them this freedom, trust, and sense that they are capable, they will come back to you. If you have a teen or tween in a rebellious stage, while not always fun or easy, know that this is quite normal development. Remember, they are trying to separate from the very people to whom they were once closely attached and on whom they depended for their very survival. It is not an easy process. What they really want is freedom, autonomy and your trust to make their own decisions. If they don’t feel that they are given this in a democratic way, they will fight, and this is where the rude behavior and power struggles appear. In my next column I will discuss some specific ways you can work through and perhaps ease teen rebellion. In the meantime, consider how far you have allowed the rubber band to stretch between you and your teen. Is it tight because you are both yanking on either end? About to snap because the tension is too much? Or is there a give and take that you can stand in even if it feels uncomfortable at times? What skills do you need to teach, or conversations do you need to have, in order to allow some stretch? Raising a teenager in today’s world can be scary at times. It can be hard to know what is the appropriate boundary for your child and how to maintain a close relationship while also allowing for separation. Don’t be afraid to reach out. Talk to family and friends. A quick internet search on “teen rebellion” will lead you to some good resources. And I am always here to answer questions or talk this through if needed. Stay tuned for my next column on July 13 for more on how to work through the stages of teen rebellion. Studies show that when we give a child a complicated toy without instructions rather than tell them how to use it, the child will find all sorts of possibilities in that toy rather than play with it in some predetermined way. If we provide our children and teens with a garden and allow growth to occur rather than a set of carpenter’s plans that tell them how to build, possibility blossoms.

In this week’s column I invite you to shift your focus from the worry about your kids to their potential. Which wolf will you feed? Feed them with creativity and possibility rather than fear, worry and anxiety. Rather than orchestrating every outcome, see her as an individual with the universe inside her. As Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young sing: “We are stardust, we are golden, we are billion year old carbon, And we got to get ourselves back to the garden.” Read on to discover the garden. Oh the possibility! JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE: Children are born with a universe of possibilities inside them. These little beings come into the world with their own temperaments and personalities that will develop based on their own innate characteristics and their relationship to the world around them. Different circumstances, environments and how the world responds to them will influence who they become. Some are born into more fortunate circumstances than others, yet it is all a host of possibilities that is inside. We see the possibility as we look into a newborn’s eyes; as we marvel at the wonder our toddlers see; as we are filled with joy when we spend meaningful time with our children or teens. And then the stressors of life come rolling in. We have to work, pay the bills, maintain a family. Through all this, there are times we feel challenged by our kids and it feels hard. Our toddlers aren’t able to do what we ask and we have to be at work on time. Our tween gives us sass because she is trying to become her own independent person and doesn’t know how to do it with grace. Our teen pushes a safety boundary because he is wired toward taking risks. We want things to happen like they do in our adult world and we are living with kids who haven’t gotten there yet. In addition to all this, fears can come creeping in. Who will my child be? Will they be OK? Am I giving them what they need? These fears influence how we respond. We feel confused or hurt, get angry, and find ourselves fighting with our kids. And sometimes we forget that what they are – what we all are – is a host of possibilities. I have to admit that I have fallen into the carpenter mode of being a parent – and talking about being a parent for that matter. In her book The Gardener and the Carpenter, professor Alison Gopnik talks about a parent as a “carpenter” who thinks their child can be molded: "The idea is that if you just do the right things, get the right skills, read the right books, you're going to be able to shape your child into a particular kind of adult." It’s as if we could, like a carpenter, create a set of plans, put all the pieces together in the right places and shape our children into adults who end up with a desirable set of character traits. While we may think it’s our job to steer our children and teens, more it might be to provide opportunities and bear witness to what unfolds. With this in mind, Gopnik also talks about a parent as a “gardener” who provides a safe and nurturing environment. Rather than worrying about and trying to control who the child will become, we let them explore and investigate, fall down and get back up and discover what works for them and who they want to be. Rather than worry about who they will be, we revel in who they are right now. “You can’t tell people what to be, I’m afraid. ... You can only love and support who they already are,” says a character in Laurie Frankel’s novel “This Is How It Always Is.” Sometimes I feel I need this pasted on my bathroom mirror. I don’t know about you, but I can have a lot of concern about my kids. While it’s not that I directly tell them what to be, it may be that my sometimes subtle messages and tone of voice that conveys approval or disapproval may be telling them who they are and what they are doing is not OK or doesn’t meet my ideals. I attempt to mold and shape and criticize and direct all in the name of protecting them and helping them get to the place where they will turn out OK. Yet it doesn’t allow them to be who they are and discover their own path. And, as another of Frankel’s characters says, it can sound as if I am saying, “Act this way, behave this way, deny yourself, or you’ll lose my love.” Or end up unhappy — or whatever it is for you. For example, rather than worrying about your kids tuning out on digital devices, can you go back to seeing them for who they really are: sparks of light and joy and fun and potential? The idea is this: Dive in with your kids about why they feel like they need that outlet for hours of the day. Investigate with them what makes it so compelling. Ask them when they feel the most happy, and when they feel the least. Explore with them other options. Provide the garden. Can we think of it as our job to teach our kids skills that prepare them for the outside world instead of shaping who they are? We can embody our values and let our children soak them up and mix them around and come out the other side with their own. Yes, it's OK to set limits, ask for kind behavior and teach your kids to contribute in the house. But, as Gopnik says, “what ends up happening is parents are so preoccupied with this hopeless task of shaping their children to come out a particular way that their relationships with children at the moment become clouded over with guilt and anxiety and worry.” I invite you to take a step back. Take a deep breath. Trust that all is well, and all will be OK. Yes, there will be bumps in the road and hard times and you may want to throw your hands up in exasperation or slump onto the floor and cry. And then go back to trust. Believe in the possibility. Believe that your children will turn out to be who they are. Provide the space. The protection. The humility. The kindness. The understanding. The forgiveness. The teaching. The love. The possibility. JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE:

Read the pairs of statements below and consider how each sounds to you: “Don’t speak to me like that!” or “Ouch. That hurts. You must be pretty upset to use words like that with me.” “Stand still!” or “Your body is telling me you have a lot of energy right now.” “Calm down. You’ll be fine.” or “You seem pretty stressed out about that test tomorrow.” “Go to your room!” or “Something doesn’t feel right to you. Do you want to tell me about it?” “You two stop fighting!” or “I hear two angry voices.” “You’re grounded!” or “You had a hard time following our agreement tonight. We’re going to have to talk about that.” We can demand that a child or teen behave a certain way, dismiss their feelings or experience, or shame them for their actions all in the name of helping them learn a different way of behaving. And sometimes these strategies can get the child or teen to do what we want in the moment. Yet what is this teaching, how is it teaching, and how does it contribute to how the child or teen is feeling? Or, we can dive in with our kids to help them think about their feelings and actions, witness our kids for who they are, show them we are on their side and eventually move toward problem solving. We can’t expect kids of any age to not have emotions, to not get upset, to not make mistakes or to know how to handle every situation with grace and kindness. From age 0 to 18 and beyond, their brains are still developing, neural pathways are rearranging, and hormones are changing. Kids need both our understanding and empathy, and they need to learn how to handle some situations more skillfully. I get a lot of parents asking me why parenting styles have changed so much from when they were raised. “When I was a kid I just did what I was told” is the argument, and I’ll address that topic in columns to come. But right now I want to ask you, of the two approaches outlined above, which feels better to you? Think about it from your perspective. Let’s say you had a rough morning at home. It was stressful getting out of the house on time and getting the kids to school so you could be at your 8:00 am meeting. You go to pull out your notes for your part of the presentation and realize you left them on the kitchen counter. As you fumble through your talk, you see your boss getting more and more angry to the point of saying something nasty to you in front of everyone in the room and later docking your pay for the week. You try to explain, but your boss won’t hear it. Now think about your child or teen in a similar situation. They tried their best. They messed up. They didn’t know how to do what you were asking, communicate how they were feeling or remember the steps they were supposed to take. You might feel frustrated and angry. You can act on those feelings as the boss in the above example did, or you can look below the surface to uncover what was going on with your child or teen to lead them to this place of dysregulation. You can give them a sense of understanding, acknowledge that we all make mistakes, talk to them about what tripped them up, problem solve and talk about how to make amends if needed. The second approach takes hard work. It’s what parent coach Lori Petro calls “conscious communication” and it takes parents stepping back before they react, observing the situation at hand and being thoughtful in how they respond. It’s easy to see a child or teen’s behavior as something that needs to be changed. And we do want to guide our kids toward thoughtful, kind behavior. Yet first our kids need to be understood. The more I think about raising kids, working with parents or engaging in any human relationship, the more I think we will all get along better if we can tell it like it is. I think of it as observing and narrating. Observe what you see happening in any situation or interaction, and narrate what you observe – and this part is especially important – without judgement: “You are so mad you wanted to hit your brother.” “You’re disappointed your friends didn’t call.” “You’re feeling a lot of pressure from school.” “You’re angry I wouldn't let you do what you want.” “You feel like I’m asking too much of you.” There is always something behind a behavior that we find challenging. If we can listen, observe and name (or make our best guess) at what the child or teen is experiencing before going into correction, blame or shame, our children will feel understood. And when our kids are validated and when they feel our empathy for their situation and feelings, they disarm (if not in the moment then often once they have calmed). They are less likely to fight back. It opens the door to communication, curiosity and self reflection. We all want to be seen and heard. It’s a basic human need. During this season I invite you to step back, take a deep breath, and turn toward your children, your partner, your loved ones and lean in. In times of challenge, dysregulation or conflict, rather than putting up your defenses or trying to change, fix or halt the behavior or emotions, try to dive a little deeper. Offer your understanding, a listening ear, a hug, and really see and hear what the other person is trying to say. You might find that the original challenge resolves itself much quicker and your relationship is strengthened in the process. “My ten year old acts as if he can't get himself out of bed in the morning even though he can and has for years. He gives up after minutes of attempting his homework. And he shies away from trying anything new. ”

“When I ask my five year old to pick up her belongings, she whines, drops what she is carrying, can't seem to put her things away, and ends up crying as if this was the hardest job in the world.” “My 15 year old refuses to look for a job. They lie around the house, are absorbed in their phone and act as if I’m the worst parent for asking them to help around the house.” “As the parent, I’ve tried everything and I don’t know what to do!” In my Nov 3 column in Jackson Hole News & Guide I write about kids who shrink away from or avoid life’s tasks. If you have a child or teen like this, they may be operating from the mistaken goal of “avoidance” or “assumed inadequacy”. How you know if your child is operating from this goal rather than one of the other three mistaken goals (attention, power or revenge) is that you, the parent, feel helpless or hopeless. As much as you’ve tried you have no idea how to help this child overcome their fears of attempting the task in front of them. Children like this are convinced of their own inadequacy and inability to succeed to the extent that they work to convince those around them of this too. They shrink, give up, refuse, retreat or complain. Their protests and lack of motivation can be so frustrating to parents that we end up giving up and often do the task for them – we enable and we rescue. Our children’s lack of belief in themselves eventually trickles over to our lack of belief in them (and sometimes it’s hard to know which came first). As Vicki Hoefle says, what this child really believes is “I don’t believe I can, so I will convince others not to expect anything of me; I can't do anything right so I won’t try, and my failures won’t be so obvious.” What these kids need is a sense of courage. And they may need our help to develop it. Read on to learn more! Instill courage in kids who avoid life's tasks JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE: Do you have a child or teen who seems unable to complete any sort of reasonable task requested of her? This is a kid who acts as if he is incapable of anything – getting out of bed in the morning, attending to basic self care, putting his gear away or helping around the house – and melts down at the smallest of challenges. They never seem to know how to do their homework, shrink back from attempting anything out of their comfort zone or are afraid to try something new. They may lie on the couch, mope around the house or shut themselves in their rooms disengaging from life. These are kids we may label as lazy, incapable, self-centered, unmotivated, entitled or disconnected. As parents we may feel helpless or hopeless. We may feel like after so many failed attempts to help there is nothing else we can do, so we give up. We have no idea how to get through to them. When looking at children and teens like this through the lens of the mistaken goals, as introduced in my April 14, 2021 column, kids who appear to be helpless, feel inadequate and ask their parents to do even simple tasks for them are working from the mistaken goal of “avoidance” or “assumed inadequacy”. Children like this are convinced of their own inadequacy and inability to succeed to the extent that they work to convince those around them of this too. This inability to feel good enough leads them to avoid any and all tasks because they have convinced themselves that they will fail. Their fear of failure and of the world discovering their ineptitude is so strong that they protect themselves by not even trying. What kids who avoid and feel inadequate need is a strong sense of courage, one of the Crucial C’s discussed in my Feb 24, 2021 column. They need our encouragement: a sense that we believe in them, see their value and that they belong. They need us to read behind their behavior and see that what they are really trying to say is, “Have faith in me. Help me develop courage. Don’t give up!” Afterall, as psychologists Amy Lew and Betty Lou Bettner say, their “failure to accomplish usually comes from a fear of failure, not laziness.” Of course there may be other factors at play. Learning differences, depression and anxiety, social challenges, past and present trauma, self-perception, and having a fixed mindset can all play a role and may warrant professional help. These factors may all lead to or stem from experiences that kids see as presenting impossible obstacles that they feel incapable of surmounting. With this viewpoint, whether a child or teen is operating from the mistaken goal of assumed inadequacy or there are other factors at play, some of the solution may be the same. These kids need strategies for building courage: Encourage experiences where success is likely. Help your child or teen find areas where they can discover their abilities. Let them work at levels where they feel adequate. Divide larger tasks into smaller more manageable steps with benchmarks to indicate progress. With successes, your child may be more willing to try incrementally harder tasks. Don’t buy in. Our kids need us to believe in them before they give us any reason to. Don’t buy into their helplessness, don’t enable and don’t rescue. Allow them to work through the challenges with support, and don’t do the job for them. Take time for training. If the task is too daunting or beyond the child’s abilities, they need to be taught some skills. Use the four step approach of 1) do the job for the child, 2) do the job with the child’s help, 3) allow the child to do the job with your help as needed, and 4) send the child off to do the job independently. Don't demand perfection. Acknowledge a job done even if it isn’t done perfectly to your standards. The more you pay attention to the positive rather than the negative, the more likely your child will want to continue doing the task. Encourage. Recognize any effort or small improvement to all members of the family without singling out this child. Say things like, “I have faith you can figure this out. I’m here for support if you need it”. Or, “It seemed like your homework didn’t cause you too much trouble today. What made it easier?” Allow for mistakes. The world is full of mistakes. Celebrate them. They are how we learn. Use Brene Brown’s idea of FFT (F’ing First Time) – normalize that we aren’t going to crush a new task the first time if we’ve never done it before. Teach positive self talk and learn about a growth mindset. Listen to how this child talks to herself. Correct him if he uses negative statements about himself. Remind them that it’s just that they haven’t learned how to do this thing “yet”. Hold limits where appropriate. This may sound counterintuitive, but if we overlook misbehavior we may be sending the message that we don’t think our kids can handle holding them responsible for their actions. Similarly, barring safety concerns, we don't want to rescue them from uncomfortable consequences of their actions. The idea is that we want to avoid giving debilitating help. Children who are operating under the idea of assumed inadequacy need your support. Spend quality time with them, notice the positive, and avoid criticism. At the same time encourage opportunities for them to overcome challenges in incremental ways. Hold them accountable, allow for mistakes, and make sure they know you believe in them. Courage builds upon itself. Once we find success in one area it can translate to a whole host of others and open up a world of possibilities along the way. JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE:

Have you ever gotten into an argument with your child that might have started with a simple request but escalated into a back and forth exchange of disrespectful comments leaving you feeling hurt and disappointed? It might look like this, as recounted by Vicki Hoelfe in her book “The Straight Talk on Parenting”, from a parent or caregiver’s point of view: ‘Our kids’ attitudes have become so bad it’s unbearable. We feel like they treat us as second-class citizens. They roll their eyes at us, walk away from us when we are talking to them, say ‘whatever’, don’t listen and don’t tell us a thing about their lives. They are rude and distant. They act like they deserve everything they get and act resentful when we ask for the smallest of help around the house. The sass, disrespect and hurtful comments have become so persistent that we don’t know what to do.’ If this sounds familiar your child might be working from the mistaken goal of revenge as introduced in my April 14, 2021 column. Children and teens who seek revenge often feel hurt and think that their only recourse is to hurt back – and this is exactly how parents with a revenge seeking child feel – incredibly hurt, angry and even attacked. “What have I done wrong?”; “Why doesn’t my child like me?”; “What have I done to be treated like this?”; “How did things get so bad?” we ask ourselves after these types of exchanges. Kids who use revenge seeking behaviors are kids who desperately want to feel that they count, or matter, one of the Crucial C’s discussed in my Feb 24, 2021 column. As human beings we have a strong need to feel significant; that we make a difference and matter to those around us; that we count. As psychologists Amy Lew, Ph.D. and Betty Lou Bettner, Ph.D say, “If a child becomes so discouraged that she feels that she is not needed, cannot be liked or cannot get her way, she may move to the goal of revenge”, and thus motivated comes “to believe that her only chance to prove that she counts is by hurting others as she has felt hurt”. This behavior can also result from children who have been frequently overpowered or overly pampered, and in the extreme abused or neglected. A child or teen who seeks revenge may believe that others are against them and that no one really likes them. They are saying, “I’ll show you how it feels” and they do what it takes to get back or get even. Often, not knowing what else to do, our response to a child who hurts us this deeply is to get angry and use punishment which only further escalates the child’s feelings of being unliked. On the other hand when we try to give positive attention, that backfires too. This child is only trying to protect himself, always on alert to preempt you before you can hurt him. What we need to understand is that these children and teens feel so hurt that they lash out trying to prove that the world is unfair. They want to punish those around them for the injustices they feel. Behind all this, what they are really trying to tell you is, “I want to count. Find something to like about me. I’m hurting”. What we need to do is slowly and persistently rebuild the relationship while also maintaining boundaries of expectations of mutual respect. And here’s the key: we can’t demand respect by escalating a disrespectful exchange or through punishment. Rather let our actions maintain the boundary by taking some deep breaths, keeping our cool, and saying, “this isn’t a productive conversation right now. I’m going to walk away and come back when we’re both in a better place”. And then follow through. Walk away and get involved in something else (or go cry in your closet if you need to). Remember that making your child feel bad only reaffirms what they already feel about themselves. Rebuilding a relationship with a child who tries to thwart your every attempt can be hard. Continue to notice the positive and eliminate criticism. Appreciate this child for what she does. Give them positions of responsibility and jobs that are meaningful. Invite them to give input, have a say in the matter and create rules together. Kids who don’t feel like they count need to be given opportunities to see that their contributions make a difference to those around them. They may see their parent’s pleas to cooperate or help out as a means of control. Thus make sure to give them meaningful jobs and comment on the importance of their work. Begin to shift your mindset about how you think about this child. It can be easy to label these kids as rude, disrespectful, mean and ungrateful. This can become a self-fulfilling prophecy and only reinforces those labels for the child, diminishing how they think about themselves. Rather begin thinking about these kids in ways that they can grow into: kind, cooperative, courageous, resilient or supportive for example. You need to believe in your child before he believes in himself or before she gives you any reason for this belief. Don’t respond to sass with sass, and as mentioned above, don’t remain in the room if sass is being thrown your way. Giving up and throwing your hands up in the air in exacerbation also sends them the message that you don’t care. The key, and this is hard, is to not take what they throw your way personally. As always, try to get into your child’s shoes. If you can tell they are hurting, empathetically notice that, offer your support and don’t give up if they don't take it the first 10 times. With time, if you continue to disengage from the revenge seeking behavior, notice and engage in the positive behavior, understand what is going on for them in their world, give them meaningful ways to contribute in the family and the home and continue to work on the relationship, over time you will see you and your child move toward a more cooperative and harmonious relationship. Imagine a power struggle as a game of catch between you and your child where the ball is the thing you are fighting over. You throw the ball to your child asking them to do something, and they throw it back at you saying “No!” You then throw it back harder: “You will do it!” Your child whips the ball back even harder yelling, “I will not and you can’t make me!” And this goes on until the game becomes about who can throw the ball the hardest until the other gives in, angry, exhausted and defeated.

What if instead we just put the ball down and tried to solve the problem? Don’t engage in the power struggle. Take a deep breath. Walk away. Lock yourself in the bathroom if your child follows. Come back and discuss when everyone is in a place where they calm and clear-headed. As Kim Lee-Own says, come alongside your child and see if you can solve the problem together. Read on for more ideas of what to do when you find yourself battling it out with your child or teen in the midst of a power struggle. What to do in the midst of a power struggle? Cease and desist. JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE: Parent: “Can you please put away your backpack?” Child ignores parent. Parent: “Honey, I asked you to pick up your backpack.” Child: “Why do I have to do it now?” Parent: “Sweetie, we had an agreement that you would pick up your things when you came home before you started doing other things.” Child: “I never agreed to that.” We know how this goes. The simple reminder escalates into a full-on argument with both parent and child angry with one another and standing their ground until they can win over the other. Winning has now become the goal and the original goal related to the backpack is diminished. But really, no one wins. No matter what we do it feels like there is always resistance. Can’t our children ever do what they are asked? My June 30, 2021 column discusses some origins of power struggles and how to avoid them, yet completely avoiding them is nearly impossible. So what do we do when we find ourselves in the midst of one? As discussed in my last column, giving our children power to avoid their need to demand it, seems counterintuitive in many ways. We can get so angry with a defiant child, who often only wants to defeat us, that we want to show them “you can't get away with this!” Don’t we as adults have to set the rules? Aren’t we the ones who are supposed to have the authority? Yet what we are doing in these moments is using our power to defeat the child, showing them that using power is the only way to resolve conflict and get what we want. We are actually teaching our children the behavior we are trying to eliminate. This child may begin to realize that she needs to work even harder to defeat us, and harder to become an autonomous individual who has a say in her world. Instead, when we find ourselves wanting to fight back with our child, what we need to do is back down. Refuse to fight while also refusing to give in to any unreasonable demands. Simply walk away. Like most parenting advice, this is easier said than done. It’s hard to walk away when we are triggered and we feel like we are being walked over. It is hard to resist the urge to overpower another when we feel threatened ourselves. Here are some ideas: Listen. To counteract our rising anger toward a defiant child, it can help to consider that underneath that struggle for power our child is really trying to tell us “I want to feel capable. Involve me and give me choices. Believe in me. Let me have a say in the matter.” Shift your thinking. It takes time, practice and patience to calm our triggers and move from reacting strongly to responding calmly. It also takes a mind shift. We often believe that there should be a complete hierarchy between parent and child. Yet we can’t raise an independent and respectful child if we don’t give them the respect and power to try things on their own. Uphold limits with empathy. By no means am I saying that you don’t create and hold limits and expectations. You just do this with empathy and understanding. Get into their shoes. Understand where they are developmentally. Think about how you might want to be treated in this situation. Using a punishment for breaking a rule or being defiant only shows them that more powerful people can push others around, making them want to use power and defiance to get what they want. Be thoughtful about what is reasonable and what is not. As our children get older, especially if we have given them the latitude to develop confidence and capability, what was once unreasonable often becomes more reasonable. Our boundaries need to expand as our children mature and become more capable. We want to make sure our limits are based on safety and our family’s individual values rather than our fear or need for control. Co-create agreements. Yes, maintain limits. Ideally we create agreements together with our children about daily rules and expectations as much as possible. Try to see their side and compromise when you can. Having agreements set in place that have been created together as a family allows us to more easily walk away when a power struggle escalates. We can use the agreement as the enforcer. This is where we refuse to fight and we refuse to give in to unreasonable demands. In the example above, the parent could walk away and later ask when is a good time to discuss their argument. The two might agree that the parent will stop disrespecting the child by nagging and reminding them, and the child would agree to do his job in a set time. If the parent forgets and begins nagging, it would be the parent’s responsibility to do the child's job. If the child forgets to do her job, the child could begin to set an alarm as a reminder, or use some other creative idea that preferably the child thinks of. You could also use psychologists Amy Lew’s, Ph.D. and Betty Lou Bettner’s, Ph.D ideas and say to the child “‘I noticed that you decided to ignore our agreement. I’d like to understand why and see if we can’t come up with a solution you are willing to stick with.’” In the moment of a power struggle, cease and desist. Let the agreement do the talking. Give your child reasonable power and control. Always question whether what your child is asking is actually reasonable or if it’s more that you feel a need for control. This is not giving up or giving in. Rather you are saying to your child that your relationship is too important to escalate the fight. When we are engaged in a power dynamic with our children or teens, the relationship can become more about who is right and who is wrong. As parents we feel angry or challenged. No matter what we do it feels like there is always resistance. Can’t our kids ever do what they are asked?

Where do power struggles come from and what are our kids trying to achieve? Read on to unpack this very common parent-child dynamic and what you can do to help your child or teen feel more empowered rather than fight you to find their power. Avoid power struggles by helping your kids feel capable JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE: From the moment children develop a will of their own, starting sometime between the ages of 18 and 24 months, they begin the process of gradually separating from their primary caregivers and developing their own identity. Throughout childhood and adolescence children are developing their own sense of self: Who am I? What do I like or not like? How do I want to dress, act and move through the world? They are also developing the crucial feeling that they are capable. This manifests in familiar ways: when your toddler says, “me do it!” or your teen responds sharply when you remind them to do something or ask them to do it your way. We all need to feel capable, to have agency, to act independently and make our own choices (for children all in an age appropriate way). If we micromanage or do things for our kids that they are capable of doing on their own, this diminishes our kids’ sense of being capable independent individuals. Children can become resentful, feel inadequate, settle into the role of being pampered or interpret our actions as being controlling. With this sense of powerlessness, sometimes our children’s only recourse is to fight. Cue the “power struggle”: In their minds disenfranchised children are saying “I’ll show you how capable I am. You are not the boss of me. You can’t make me do it!” Sometimes the need for one’s own power becomes so strong that the fight is not about what the parent is asking, more it’s about doing anything not to give in to the parent’s requests. It may not be about doing the homework, setting the table, brushing the teeth, observing curfew, or maintaining agreed upon limits of any kind. It’s about gaining control through defiance. “If you don't believe I’m capable, I’ll show you what capable is!” They roar, they tantrum, they defy. The will to become autonomous is that strong. While some of this is natural adolescent development, teens who feel disempowered may show their power by resisting our attempts to guide them and instead show that they can do whatever they want whenever they want. They may try to prove their competence by taking unnecessary risks. What do our children and adolescents need? From day one they need us to believe that they can handle situations that come their way. That they can overcome a challenge. That they can take care of themselves. That they can contribute to their family or community. That they can help others. What does this look like? It means allowing your child to try things on their own, to struggle to meet a challenge, to make their own choices and their own mistakes – all in an age appropriate way and in stepping in when the task at hand is far beyond their capabilities or realms of safety. More specifically, allow your baby to whimper a bit to see if they can self soothe, and comfort them if they can’t. Put a toy just out of reach to see if she can squirm a bit to grab it. Let your toddler decide what to wear on any given day with confidence that he may learn what works or doesn’t given the weather, social norms or his personal preferences. Help your child set their own morning and bedtime routines. Allow your child to help with chores even when they are at an age where their help may actually be a hindrance. Don't do things for your kids because it is easier or will avoid an emotional upset. Have open conversations about curfew, dating, screen time, substance use and risky behaviors. Provide an opportunity for your teen to share without your judgment. Then actually listen and consider their point of view. Compromise where you can and be willing to muddle through the challenging process of co-creating agreements. Taking these steps communicate a powerful message: that you believe in your child and their capabilities. That you trust them. That they don’t need to demand power over others because they are empowered in their own self and their own abilities. As parents we have years of life experience. We know how things work, and it feels like it’s our job to impart this wisdom to our kids. Yet we know how things work for us. Our children and teens want to learn how things work for them. Again within the realm of safety and your child's age, relinquish as much control as you can while also maintaining agreed upon limits and expectations and a kind, loving and respectful relationship. At the end of the day we also want to look at the bigger picture – the long term goal of raising kids who are self motivated, take on responsibility and know how to take care of themselves; kids who feel empowered to try things on their own and who are not afraid to make mistakes; and kids who feel confident not only in their decision making but also in who they are. None of this can happen if they aren’t given the opportunity to feel capable and empowered. Interested in discussing the idea of helping your children feel capable and empowered in your home? Schedule a coaching call with Rachel either individually or with a group of friends at fees that work for your individual budget. Thanks to Vicki Hoefle and Amy Lew, Ph.D. for inspiration for this column. Children seek extra attention as a way to connect

JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE: You know you have an attention-seeking child if you have a child who always interrupts you when you are on the phone, picks on siblings when you are busy, wants to play when you are working or cooking, is always forgetting things, becomes mischievous or doesn’t follow through on agreements or constantly asks “why?” You find yourself repeatedly nagging, reminding or otherwise engaging. Attention-seeking children keep us busy with them by requiring that we repeat ourselves several times in order to get them to complete a task or come back even when we have told them “not now.” What do we do? We say, “In a few minutes,” we answer the incessant questions or we find ourselves continuously breaking up sibling fights. Our repeated responses, even if negative, are actually giving the child what he or she wants — our attention — and thus reinforcing the misbehavior. It can leave us feeling frustrated or annoyed by the repetitive demands. There are two kinds of attention: positive and negative. Children may be a high-attention-needs kids if (1) they have become accustomed to having your frequent attention and have developed the idea that they need your attention in order to feel significant, or (2) they don’t get enough of your positive attention, so they resort to negative behaviors to get the attention they feel they are lacking with the idea that negative attention is better than no attention at all. Children need our attention. Receiving attention and being noticed feels good, gives children a sense of belonging and helps them feel connected. We want our children to know they belong for who they are and for their contributions, participation and cooperation in the family, not from keeping us constantly engaged with them. While children might want our full-time attention, it is not realistic or appropriate for parents to give this kind of attention 24-7. The need for attention becomes challenging when this attention is the only place from which a person derives his or her self-worth. It can go to the extreme to where children may begin to believe that they have a place in their family only if they are being noticed or if they keep others busy with them. That is the mistaken goal of desiring undue or extraordinary attention, as introduced in my April 14 column. Parents who have high-attention needs-children come to me baffled: “But I give my child attention all the time!” We have to understand that these children have developed a misguided belief that their worth and ability to belong comes from this attention, so they want more of it. Whatever we give is never enough. Rather, we want our children and teens to know that they are important even if we are engaged in something else. We want them to feel securely connected through our unconditional love and through their ability to find belonging through cooperation, participation and contributing to the family. So, what do we do if we find ourselves living with a child who has developed the mistaken goal of seeking extraordinary or negative attention? First, decode the message they are sending. These children are not being bad kids. Rather, their hidden messages are, “Notice me. Involve me in something useful” and “I want to connect. Catch me being good.” What we want to do is pay attention to our children’s positive, cooperative and productive behavior. To do this we have to allow space for these situations: Carve out time to engage in child-directed activities or stop what you are doing to make eye contact and really listen. For example as Dr. Richard Dreikurs says in his book “Children: The Challenge,” if our kids’ “quiet moments of constructive play brought a warm smile, a pleased hug and a [word of acknowledgement], they would be less inclined to get our attention through disturbing behavior.” At the same time begin to quietly ignore the negative attention seeking behavior and create limits around their demands: “I know that you want me to play with you. I am busy now. If you can be patient and play by yourself for 10 minutes, I’ll be able to spend some time with you then.” If your children are used to you giving into their attention seeking demands, this may be hard for them at first. They may demand your attention louder. They may cry, whine or find mischief. But if you remain firm and kind, soon your kids will find other, and perhaps with some teaching, more useful behavior that meets their needs for connection and belonging. Our natural anger and frustration at their incessant demands for our attention only make things worse. What we need to do is notice our children and involve them usefully. Connect through play, a shared activity, making family plans or cooking a meal. Bring them into household responsibilities. Give positive attention, schedule time together, appreciate the big and little things your children do, recognize strengths and talents by asking them to teach you about one of their interests, and accept your children for who they are. Working with a high-attention-needs child can be challenging, and of course there are nuances and various perspectives about what course to take. There is no prescribed formula. Every child and every situation is different. That’s why it is important to look at the needs of every situation, including the needs of yourself and your child, before you move forward. Sometimes our children’s bids for attention are a matter of needing to learn skills or work through challenging emotions or of being exhausted at the end of the day. If you would like to discuss this more and talk about what this means for your situation, please join the Parent Talk discussion June 1 at 6 p.m. (find info at GrowingGreatFamilies.org) or schedule a coaching call with me at fees that work for your individual budget. Thanks to Amy Lew, Ph.D., for inspiration for this column. Dear Parents and Caregivers,

I’ve recently picked up child psychiatrist Rudolf Dreikurs’ book “Children: The Challenge”. It’s a classic and some of the examples are outdated yet the philosophy about what children need and what motivates their behavior is so right on. It is this philosophy, originally developed by psychologist Alfred Adler, that is the foundation for many parenting programs including Vicki Hoefle’s work and “Positive Discipline”. The idea is that all human behavior has a purpose and that purpose is to attain some sort of goal. We are social beings, and as such our ultimate goal is to feel a sense of belonging and significance within our immediate group (the first of which is our family). As such a child’s behavior is a means to attain the basic goal of feeling they belong and finding their place in the family. Through trial and error and by trying on different behaviors children decide which behavior works to get their needs met. As Dreikurs says, children will “repeat the behavior that gives them a sense of having a place in their family and abandon that which makes them feel left out”. If productive behaviors don’t give them this sense, they will try on “misbehaviors” to see if this new way of acting gives them a better sense of belonging. Interested in understanding more about how this works? Read on! A misbehaving child is a discouraged child JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE: “My child needs my attention 24-7.” “Every interaction with my child ends up in a power struggle.” “There is so much disrespect in our relationship.” “My child has given up and won't even try.” In my Feb 24 column I talked about how behaviors are goal directed – they are attempts to get certain needs met. These needs can be summarized by the Crucial C’s as stated by authors Amy Lew, Ph.D. and Betty Lou Bettner, Ph.D. as "connection to others, to be capable of a degree of independence, to count as a member of the family and the community, and to find the courage to meet life's demands and seize its opportunities." Children will try various behaviors to get these needs met. When they try out constructive behaviors (asking for help, wanting to do things on their own, kindly stating their opinion) and their needs are met (parents pay attention, allow independence, give their children a say), then these behaviors will become part of their life’s strategies and how they interact with others. However, if children’s needs don’t get met through constructive behaviors, for example if their efforts are met with criticism, lack of respect or dismissal, children will often feel discouraged and try out “misbehaviors.” A child may begin to whine, engage in power struggles or defy agreements in order to feel connected, capable or that they count. While it may sound counterintuitive, sometimes these misbehaviors, which are based on the child’s mistaken belief about how to achieve the Crucial C’s, do meet the child’s needs. These behaviors then become part of a child’s strategies and how they interact with others. There are four mistaken goals of behavior that correspond with the Crucial C’s: Attention. Children who don’t feel connected will often seek out undue attention in order to feel that they belong. Their mistaken belief is “I belong only when I have your attention. These are the children who are always needy, occupying every minute of your time. Power. Children who don’t feel capable and are not given the chance to independently take care of themselves and contribute to their first community (their family) may feel inadequate and begin using power as a way to feel capable. Their mistaken belief is “I belong only when I’m the boss, or when I won’t let you boss me around.” Their power comes from the feeling that “You can’t make me!” They may seek control over themselves, others, or the situation at hand. Revenge. Children who don’t feel that they count or matter, often feel hurt and insignificant. These are children whose efforts go unnoticed, or may not feel needed or liked. They may feel so hurt that they try to get revenge by hurting others. Their mistaken belief is “I don’t belong. I knew you were against me. At least I can hurt back.” Avoidance. Children who don’t have courage often feel they are not good enough. This feeling of being inferior can lead them to avoid. This can show up as assumed inadequacy or helplessness. Their mistaken belief is “It is impossible to belong. I can’t do anything right. I might as well give up.” These are the children who give up, shrink back up or don’t want to try. Their thought is that it is better to not even try so no one sees their inabilities. It’s important to note that sometimes our children’s physical and emotional development and brain maturity isn't quite there for them to use productive behaviors to get their needs met. Sometimes they don’t have the skills to ask politely, control their impulses and regulate their emotions. Sometimes they don’t have the knowledge of what appropriate behavior is in a certain situation. This is when we have to be really aware of what our responses to our children’s challenges are teaching them. Are we modeling the behavior we want to see, connecting with our children empathetically and teaching skills? Or are we responding with anger, punishment, criticism or shame and thus discouraging our children which may lead them toward the need for misbehavior? If we go by the theory that “a misbehaving child is a discouraged child” as psychiatrist Rudolf Dreikurs writes in his book “Children the Challenge,” what we need to do is investigate where the discouragement lies. Which Crucial C is my child not feeling? What is my child’s belief, or even mistaken belief, behind the behavior? How do my responses contribute to his belief? How can I encourage my child and help her develop a more positive belief about herself? In my next four columns spaced at 6-week intervals I will dive into these mistaken beliefs in more detail using concrete examples, giving ideas about how to encourage the discouraged child toward behavior that gets their needs met in a more productive way. If you would like to discuss these ideas in more depth, join me for my “Parent Talk” discussion group via Zoom at 6pm on April 21. Find details here. Rachel would like to thank Amy Lew, Ph.D., and her book “A Parent’s Guide to Understanding and Motivating Children” for inspiration for this column. Parents often come to me baffled by why their children are behaving a certain way. Rightly so. The hitting, screaming, whining, vies for attention, snarky responses, disrespectful attitude or defiance. We are good parents. We take care of our children, love them and give them what they need. Why do they get so upset or treat us so poorly?

There is a purpose for or reason behind every behavior, and it's often an attempt to reach some sort of goal. The first step in working with your child or teen's challenging behavior is what I call becoming a "behavior detective" – understanding where that behavior is coming from. The topic of behavior development can be complicated and by no means will I be able to cover it all here, but in general a child’s behavior develops from a few simple places: genetics, brain development, interaction with others and the environment around you, and an attempt to get certain essential needs met. In my most recent column I talk about behavior as developing in a social context – within the relationships we have in our families. It develops as a result of how we are responded to, what others believe about us and the strategies we use to get certain crucial needs met. Read more below from my Feb 24, 2021 column in the Jackson Hole News & Guide. Be well, go hug your kids, and take good care of yourselves and others. With love and faith in you, Rachel Behavior Development and the Crucial C's JACKSON HOLE NEWS AND GUIDE: Whining. Disrespect. A snarky attitude. Not listening. The list can go on. Sometimes it can be hard to understand where a child’s behavior is coming from. A child’s behavior often develops in a cause and effect relationship with their parents or caregivers. The cause is the child’s behavior. The effect is the parent’s response. If this response is consistent, the child soon learns that if I do X, then Y will happen. If Y is something the child desires, then they will continue to do X in order to get what they want. However, if Y is not what they desire, they will soon stop doing X. Let’s use the classic example of a whining child. Child whines and parents do one of two things: parents either respond by giving the child what they are asking for, or parents will say, “stop whining”; “use your big boy voice”, or “I can't hear you when you talk like that”. Either way, child gets a desired outcome – parent’s attention. What if parent didn’t respond at all? Child whines and parent keeps doing what they were doing or acts like they didn’t hear the child. Parent simply ignores and moves on. This may sound a little harsh at first, yet hear me out. Child may get confused. Whining has always worked in the past, why isn’t mom or dad responding? So child may whine harder and louder to get parent’s attention. But you, the parent, are committed and won’t be broken. The whining is hard on your ears and has an impact on your relationship with your child since you end up frequently frustrated. Thus you stay calm and move on to something else. Then suddenly, at some point, out of nowhere your child asks for your attention using a clear, kind and normal voice. What do you do? You drop everything and give your child attention immediately. “Ah”, thinks the child, “this is what I want - mom or dad”. And if this pattern continues child will soon learn that using a regular voice (X) gets me what I want – mom or dad (Y). To confirm this you may note that your child does not whine at school, because the teacher does not respond to the whining – the child knows the strategy of whining to get attention only works with her parents. This is what it’s about. Behaviors are strategies we all use to get our needs met. As psychologist Alfred Adler puts it, behaviors develop as a result of how we are responded to by others in our world. As a child these “others” are typically our parents or immediate caregivers. Psychologist Amy Lew has described it like this: as a child when we are born into a family, it’s as if we are born onto a stage and we are trying to figure out our role in the play without a script. We look to the other actors to determine our lines. We wonder if we are an understudy or if we are in the spotlight. We determine our role based on how we are responded to, our relationship with the other actors, and how we feel the others think about us. Behaviors are thus directed by the goal to get certain needs met. If we can achieve this goal, we feel capable. We feel good that we can do something that takes care of our needs. We have a positive outlook of ourselves. If we can't achieve our goal of meeting these needs, we may become discouraged. This is where misbehavior can emerge as the child uses other means to meet their goal. What are these needs – the goals that children are trying to achieve? Many will describe them using different words but they all boil down to the same thing. Using psychologists Amy Lew and Betty Lou Bettner’s “Crucial C’s”, “all human beings strive to fulfill their needs to be connected to others, to be capable of a degree of independence, to count as a member of the family and the community, and to find the courage to meet life’s demands and seize its opportunities.” Connected. We all need to feel that we are loved and accepted for who we are, that we are safe and secure and that we belong. This is not just a psychological need, it is also a physical need. As a young child we cannot survive unless we are connected to a capable adult. As children we will try different ways to relate to others and find the connection we need, and these strategies become part of our behavior. Capable. We all need to believe that we are competent human beings, capable of taking care of ourselves and the world around us. We need to feel that we have efficacy – that we can enact change, meet our goals and create a desired result. As children we have an innate desire to strive for independence. The strategies we use to move toward becoming a capable and independent adult become part of our behavior. Count. We all need to know that we are significant, that we are valued and that we matter. We need others around us to notice that we make a difference. As children, the attempts we make to feel valued, and whether or not we feel like we count to those around us, will impact our behavior. Courage. We all need to feel that we can overcome challenges, that we have the courage to get up from a fall, that we can solve problems, and at times, tackle things that we don’t necessarily enjoy. Life is filled with challenge and risk, trial and error. Whether or not we have the courage in ourselves and the belief of others in our abilities plays a role in how we behave. Yes, there are other factors that impact our children’s behaviors. Genetics, brain development, feeling tired or stressed and societal impacts all play a role. Yet we are social beings developing in a social context and we cannot separate our development from our relationship with those around us. So whether you are raising a toddler or a teen, start thinking about the cause and effect of your interaction with them. Does how you respond bring about a desired effect or behavior (the Y)? If not, how can you switch things up? If you are interested in diving deeper into these ideas, join me and other parents on my periodic “Parent Talk'' discussion group. Find more here. Photo by Ray Hennessy on Unsplash Dear Parents and Caregivers,